Choosing to Drink: How Voluntary Alcohol Exposure Changes the Brainn

- Olivier George

- Jan 27

- 3 min read

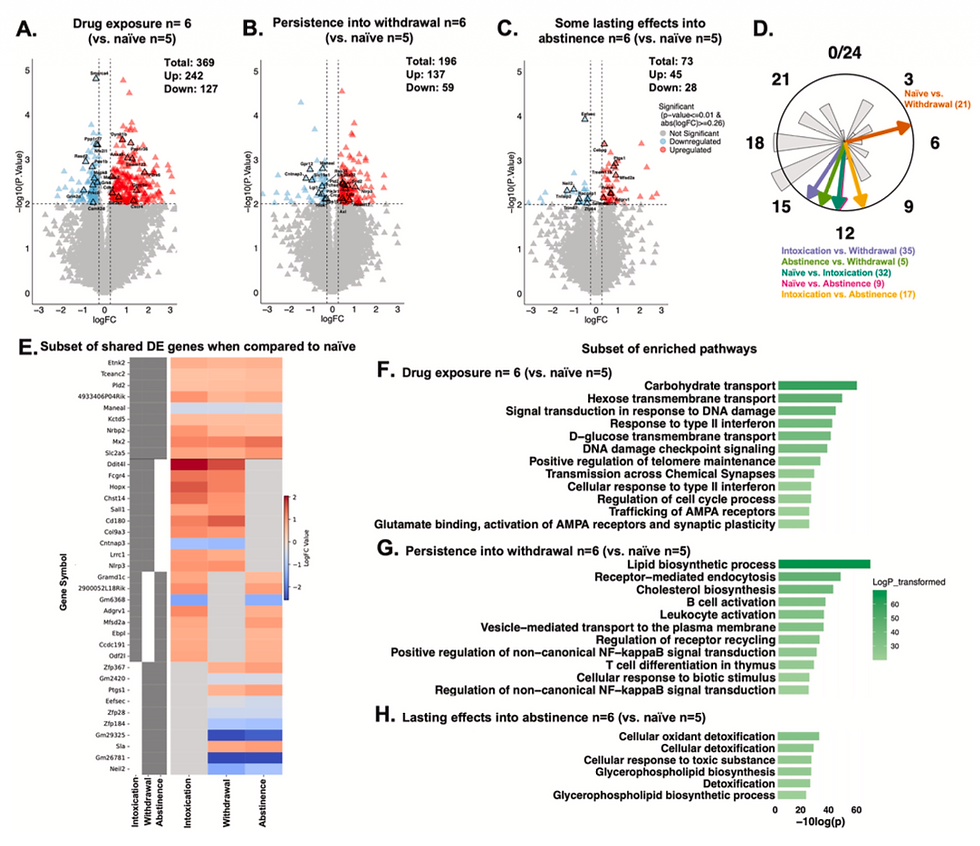

When we study alcohol addiction, we often look at how the brain responds after long periods of heavy use. For years, the standard way to study this in the lab was through "forced" exposure, where subjects are passively given alcohol to reach high levels in their bloodstream. However, we recently developed a new way to look at this process by allowing subjects to choose when and how much alcohol vapor they breathe in, a model we call Ethanol Vapor Self-Administration (EVSA).

In our latest study, we wanted to see if voluntarily choosing to reach high blood alcohol levels leads to different brain activity than being forced to reach those same levels.

The Big Question

We set out to answer two main things. First, does choosing to breathe in alcohol vapor eventually lead to an escalation in actual alcohol drinking later on? Second, even if the drinking behavior looks the same, does the brain use different "circuitry" when the addiction was started voluntarily versus passively?

Exploring the "Voluntary" vs. "Forced" Brain

To test this, we compared two groups of rats. One group was voluntarily exposed to alcohol vapor (EVSA), while the other was passively exposed through a standard forced-air system (CIE). We made sure both groups reached the same high blood alcohol levels. After four weeks, we measured how much they drank during withdrawal and looked at which neurons were active in key brain regions related to stress, reward, and habits.

What We Discovered

On the surface, the behavior looked almost identical. Both groups showed a significant escalation in alcohol drinking and a high motivation to seek it out during withdrawal. But when we looked under the hood at the brain’s activity, the story was very different:

Shared "Stress" Activity: Both groups showed similar high levels of activity in the Central Amygdala (CeA), a region famous for its role in stress and the negative emotions associated with withdrawal.

Widespread Recruitment in the Voluntary Group: In nearly every other region we checked, the "voluntary" group had much higher neuronal activity than the "forced" group.

Goal-Directed and Habit Centers: We found that choosing to take alcohol specifically recruited the Dorsomedial Striatum (DMS), which is involved in goal-directed actions, and the Paraventricular Nucleus of the Thalamus (PVT), a critical node for motivation and stress.

Stronger Connection to Drinking: In the voluntary group, activity in the habit and reward centers (DMS and Nucleus Accumbens) was directly tied to how much alcohol they consumed, a connection that was missing in the forced group.

Why This Matters

This research highlights that the way someone enters addiction—voluntarily versus through external pressure—might change the neural networks responsible for maintaining it. We found that the voluntary model engages brain areas like the DMS and PVT that passive models simply do not.

By understanding these unique "voluntary" circuits, we can better target treatments for the actual human experience of alcohol use disorder, which is defined by the volitional, though often compulsive, choice to drink. We believe this is a vital step toward discovering pharmacological treatments that address the specific brain regions responsible for maintaining addiction in the real world.

Reference: de Guglielmo, G., Simpson, S., Kimbrough, A., Conlisk, D., Baker, R., Cantor, M., Kallupi, M., & George, O. (2023). Voluntary and forced exposure to ethanol vapor produces similar escalation of alcohol drinking but differential recruitment of brain regions related to stress, habit, and reward in male rats. Neuropharmacology, 222, 109309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2022.109309

Comments